The Moss gearbox used on Jaguars up until 1965 was made by the Moss Gear Co. of Birmingham, and is generally considered very durable, though of course there are exceptions. Repair manuals issued by Jaguar Cars, Ltd. were published at the time the cars were current models, and were intended for repairing the cars when they were still fairly new and spare parts were plentiful. They are available as reprints, and it will be assumed that the reader will have already purchased them.

They of course do not cover cars that are now 30- 50 years old and have been neglected, run into the ground or bodged up by previous owners. This dissertation will describe some aspects of the repair of these gearboxes which are not covered in the factory manuals. If your restoration project car is in driveable condition you might consider a short road test to evaluate the condition of the gearbox before beginning the restoration teardown. However, if you are dealing with a car that has not turned a wheel for many years, you should disconnect the speedometer cable from the speedometer before you move the car even ONE INCH.

The reason is that the odometer and trip meter have little fiber gears inside which may have gotten stuck with old hard grease and years of inactivity, and if the cable turns even a part of a revolution it will shear off a couple of teeth on these little gears. Guess how I know. There is normally some noise in first and reverse gears because they are straight cut rather than helical. I hope it doesn’t make any broken tooth noises, because nobody seems to have any replacement gears for these things. Bearings, gaskets and shaft seals is about all you can get for them anymore. The second gear synchronizer may have some wear and thus not shift as smoothly as it should. This can usually be cured with lapping compound, and even in a case of extreme wear a machinist can still save it.

The input shaft bearing may have some wear, causing noisiness when idling in neutral. If you have driven the car and know it shifts ok and doesn’t make any worn-bearing-like noises, a complete disassembly may not be necessary; restoration of the gearbox could be just a matter of cleaning and painting the outside of the cast iron maincase (black), applying sealant in between the various castings, and replacing the old leather shaft seals with modern rubber lip seals. Mine had leather seals made by George Angus & Co. of Wallsend on Tyne.

The gearbox should be filled to the dipstick mark with SAE 30 or SAE 10W30 engine oil. Do not use SAE 90 gear lube because it will hinder the smooth operation of the synchronizers. Stuck in First Gear? The Moss gearbox as originally installed in 1954 and earlier cars has a fundamental design flaw that only causes a problem after the gears become rather worn. The problem is that it gets stuck in first gear. It is particularly common on the XK120, as some drivers had the habit of speed shifting and chirping second gear, but it can happen on Mark V, VII and other earlier and later models as well.

If this happens to you, STOP THE FORWARD MOTION of the car as quickly as you can in safety, get the car over to the side of the road, and don’t try to go any further, but if you are in a precarious position you can creep along very slowly until you can pull off safely. The reason you can’t just keep going is that the car is in first gear but the second gear synchronizer cone is trying to synchronize to the speed of the second gear wheel cone. which it can never do, and so the two will burn themselves up if you try to drive even a couple of miles at any speed faster than your grandmother can walk. Do NOT use brute force on the gearshift lever, because you might bend the synchro fork. Try shaking it around and it just might slip into neutral as if nothing happened. If that doesn’t work, call a flatbed tow truck. If for whatever reason you have to tow it with the rear wheels on the ground, disconnect the driveshaft at the rear axle before towing it home. You might want to make a photocopy of this page and keep it in your cubby box, so that if some day years from now it happens to you, you won’t be wondering “what was it that guy had to say about getting stuck in first?” As you have probably already guessed, it happened to me.

The Roadside Fix If you are far from home and you don’t want to tow it or you don’t trust the local transmission repair shops with an unusual job like this, believe it or not if your car has a removable gearbox tunnel you can actually do a roadside repair with just ordinary tools. You will need two big flat blade screwdrivers and a 5/16 BSW socket wrench. Remove the shift knob, front carpeting, padding and the gearbox tunnel cover. Remove the gearbox dipstick and gearbox top cover. Careful, it’s oily, don’t let it drip all over your seats. Now you can see the gears. The big one at the rear with straight cut teeth is first gear, and on the front side of it you will see some small ball bearings hanging out in between it and the second synchro sleeve that the first gear is supposed to slide on.

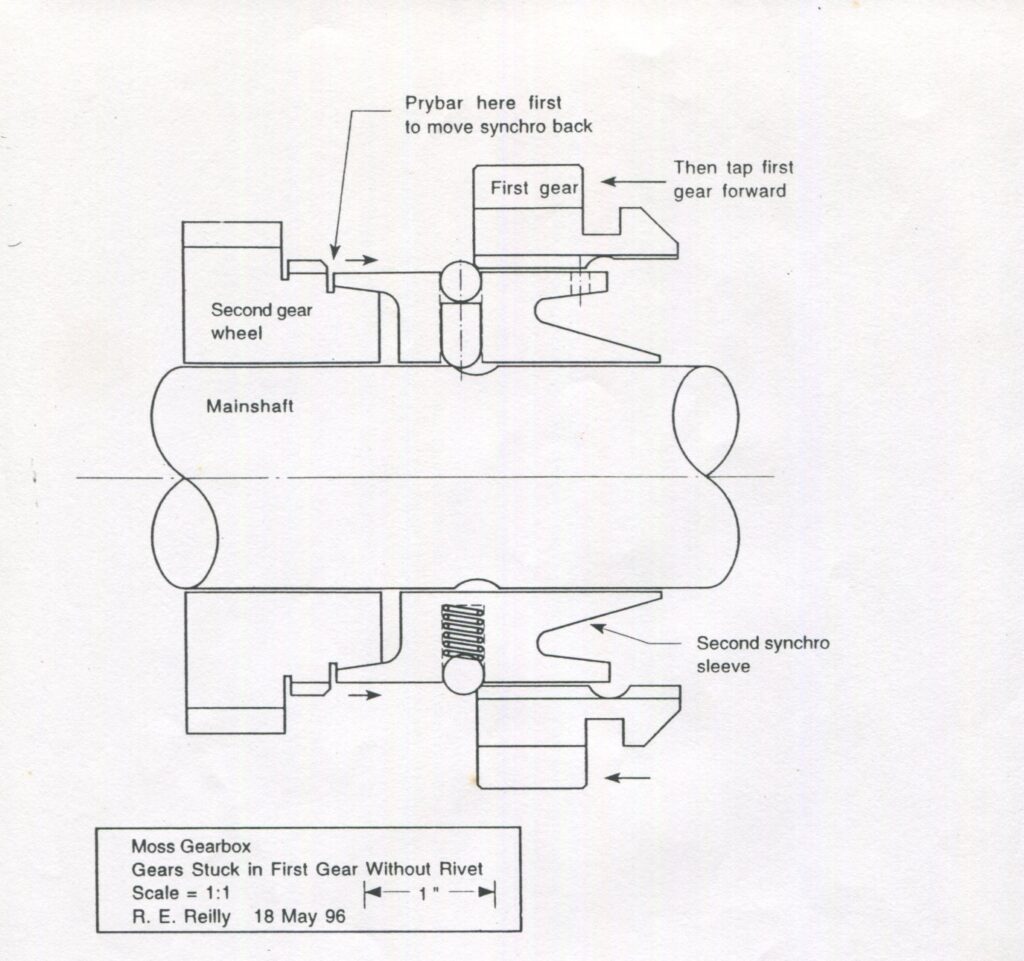

There are six evenly spaced spring-loaded balls (though you can only see two or three) and a seventh in between two of the six that has a solid plunger pin hidden under it. What you want to do is pry the first gear forward into the neutral position. HOWEVER, DO NOT USE BRUTE FORCE ON IT, no hammer and chisel please, because that seventh ball with the solid plunger pin behind it is preventing forward motion and hammering on the gear will only cause damage to the mainshaft. To drive the first gear forward you must FIRST pry back the second synchro sleeve rearwards away from the second gear wheel. The second gear wheel is the rearmost of the gears with angle cut teeth (this is what is called a helical gear, incidentally), and it also has small boat-shaped teeth to the rear of the helical teeth.

The second synchro sleeve is just to the rear of the boat-shaped teeth, and will likely be pressed up against them, though its own teeth may or may not be lined up with them. Put a screwdriver or prybar in between the synchro sleeve and the boat teeth. Pry it back rearwards about 1/16″ or the thickness of a big screwdriver blade and hold it, then gently pry the first gear forward. It should slide into neutral position. Now you can put the shift lever in neutral position and put the top cover back on and if you’re very careful and promise NEVER to use first gear you can drive home. Or if you have a bit of wire you can turn the top cover over and wrap the wire around the rearmost exposed portion of the center fork operating rod, which will limit the fork travel and thus stop first gear from engaging too far to the rear.

If you find wire or a washer already on there, you know someone has already had the problem and did this quick fix. Apparently it was common in the good old days for repair shops and even dealers to fix it this way. However, it’s not the best solution because it reduces the amount of tooth engagement in first gear, thus increasing the stress on the teeth. See below for the real fix. If the balls and springs have all fallen out, then at least you’re not stuck in first, and hopefully all those little parts will fall to the bottom where they won’t hurt anything, but if you drive it the second synchro sleeve cone will rub against the cone of the second gear wheel at a different speed in any other gear except second, so it’s probably better to drive home using ONLY second gear all the way, or call a flatbed.

The Real Fix The factory made a change in about 1954, incorporating a stop pin on the second gear synchro sleeve to prevent this problem, and issued a service bulletin that the new sleeve with the pin should replace the old pinless sleeve when rebuilding an older gearbox. The pin is pictured in manuals of some later models such as the E-type. If a gearbox made after 1954 gets stuck in first gear, it is because the stop pin has been sheared off by hard shifting. If you have a pre-’54 gearbox, a stop pin can be added to your original sleeve, and if the gearbox is disassembled for other reasons I strongly recommend you add one now.

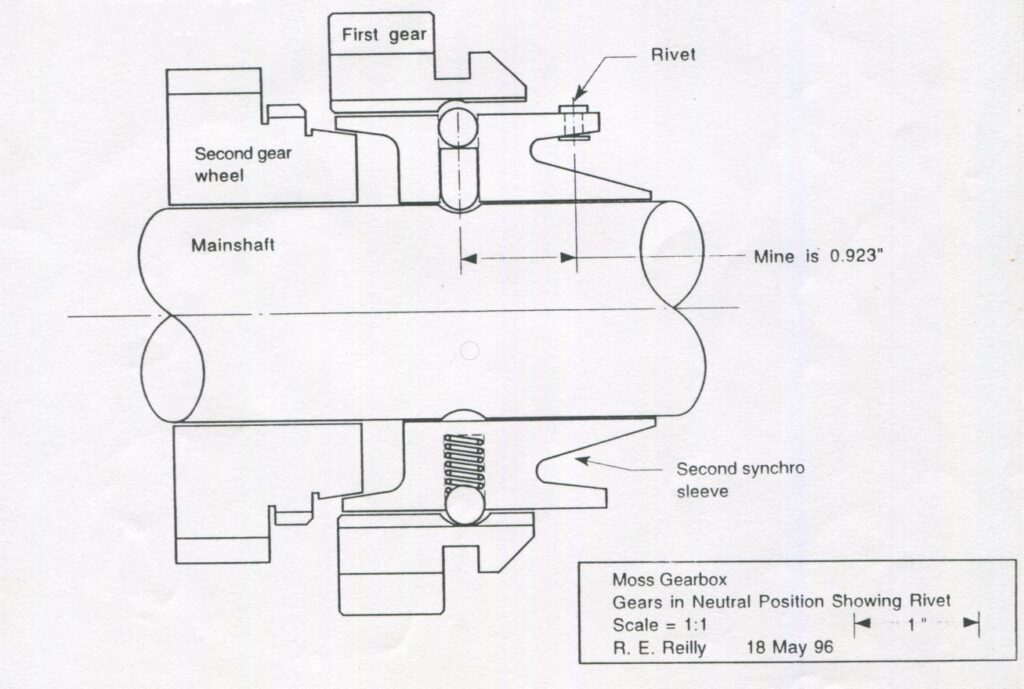

The stop pin is in reality nothing more than an ordinary rivet which is flattened out and filed off to the correct height. The rivet is placed so as to stop the first gear just before the point where the balls would pop out. Notice in the shop manual there is a reference to a relieved tooth inside the first gear. This tooth passes over the stop pin, but the unrelieved portion of the tooth bumps up against it, thus stopping the gear from moving too far to the rear. To add a stop pin, the sleeve must be drilled, but since it is hardened steel that is harder than a woodpecker’s lips, making a hole in the sleeve is a job for an expert machinist with a carbide end mill.

The exact placement of the hole requires careful measurements and calculation based on the size of your rivet and the depth of the relieved tooth. Mine turned out to be 0.923″ center of plunger hole to center of rivet hole, which I achieved by setting it up in a Bridgeport mill. Tips for Disassembly and Reassembly When separating or assembling the sliding gears with their sleeves, hold them in a box or bucket so the little balls will be caught when they fly out. Take note of the number of shim discs under the ball springs, which are there to adjust the spring tension on the balls. The discs may be stuck at the bottom of their holes.

The balls and springs are all the same, but the plungers may be three different lengths, so take note which came from where. While you have the gearbox apart, take the opportunity to lap the second synchro, which means to rub the inner and outer cones together with valve grinding compound in between. This will help it shift into second without chirping. The 3rd/4th synchro is less likely to need this lapping. Also dig or chip out the burned metal that has built up in the longitudinal grooves on the inner cone. In a case of extreme wear the front face of the second synchro sleeve may rub against the rear face of the second gear wheel.

If yours is this badly worn, don’t despair, take them both to a good machinist and ask him to turn off a few mils on the front face of the second synchro sleeve in a lathe. A “mil” is one thousandth of an inch. I cut 25 mils off mine and now it shifts like new. I nearly got bitten by a serious flaw in the official factory shop manual for XK 120-Mark 7, in the section on gearboxes. My 3rd/4th synchro sleeve has two plungers and two relieved teeth, one forward and one to the rear, and the 2 notches in the mainshaft are offset; thus it can go on the mainshaft six different ways but only one way is right. The manual says nothing about this little fact.

It just says to assemble the sleeve to the mainshaft. Apparently the paragraph as written on assembling the 3rd/4th synchro only applies to the earliest SH type box, or maybe the whole paragraph was simply cut and pasted (not on a Macintosh, I mean literally by some office girl with scissors) from an earlier manual like the Mark 4 or SS 100. If I hadn’t noticed this I would have got the gearbox together and then not been able to shift into 3rd and 4th. In “Complete Official Jaguar E”,

I see they have added a couple of paragraphs and pictures explaining this in detail. Another discovery I made was that you have to tighten the tailshaft nut all the way, thus pulling the mainshaft bearings to their proper places in the tailcase, and then back off on the nut just a bit to relieve the preload on the bearings. If you don’t do this the mainshaft will be too far forward and the 2nd and 3rd gears will be out of alignment with the countershaft gears. Once again the manual says nothing about that.

Clean and oil everything, do not paint any part that goes inside. Do not blast away that red paint on the inside of the maincase; it is there to seal in microscopic sand particles embedded in the rough cast surfaces. Get a 1″ diameter wood dowel rod cut to just the length of the countershaft plus the brass spacers, about 8- 1/2″. Assemble the countershaft gears, bearings and spacers on it. Then drop it into the case, and when the mainshaft is in place, the countershaft gear cluster is lifted up into place and the dowel is pushed out the front or rear hole by the real countershaft.

Use a good engine assembly sealant in all bolted joints, not silicone RTV, and don’t forget to put some on the countershaft and reverse gear shaft ends. Many of the internal parts of my gearbox were marked “G.G.Co.”, for which I never did find an explanation. Presumably it is the trademark of some small gear company that made parts for Moss Gear. The Speedometer If you buy a used speedometer that has been sitting on a shelf for umpteen years or has just been pulled from a parts car, whether from a private party or a used parts vendor, ask them NOT to stick a screwdriver into the drive hole and give it a twist to see if the needle moves.

Not only is this not a valid test of the accuracy of the instrument; it also risks destroying the little fiber gears inside that operate the odometer and trip meter if they have gotten stuck with old hard grease and years of inactivity. If the seller insists on a test, have them hold the gauge in one hand and just flick it. As long as the needle moves freely and returns to zero, pronounce yourself satisfied and take it home, where you can take the mechanism out of the case and clean and oil those little gears BEFORE trying the screwdriver twist test. A better test would be with a reversible electric drill motor and a Robertson square drive bit insert, being careful about which direction it turns. The mechanical type tachometer (rev counter) can also be tested this way, but note it turns the opposite direction and has no little gears inside to worry about.