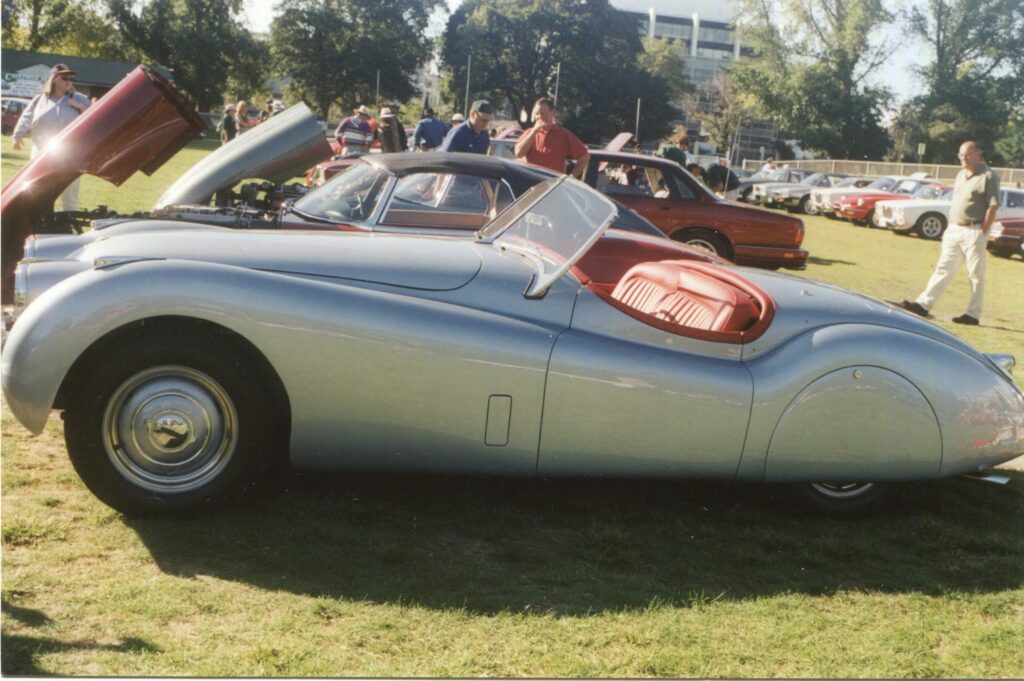

In 1951 Jaguar recognized the customer interest in increased performance by making available a modified version of the XK-120. For an extra $395 the customer received stiffer front torsion bars and stiffer rear leaf springs, racing wire wheels, dual-exhaust system, a camshaft with a higher lift, lighter flywheel, and a special vibration damper.

This brought the output up to 180 B.H.P. at 5300 rpm; 203 ft-lb of torque at 3500 rpm. In a test of the modified engine in a coupe body it showed a creditable improvement in acceleration throughout the entire speed range. From 0 to 80 in 14.9 seconds is phenomenal for a mass-production, inexpensive car. The top speed, 123.3 mph, is almost identical to The Motor’s 1950 test of one of the first XK roadsters made. Their clocked average of 124.6 mph, made with a 3.64 final ratio, is just over 1 mph higher than was achieved on the coupe with a 3.77-to-1 axle ratio.

The flexibility of the Jaguar modified engine is one of the big reasons for the appeal the car has for the average driver. It will accelerate smoothly from 15 to 120 mph in top gear. The most practical cruising gear for city driving is third and, except for formal and informal competition, there is never any need to use more than two of the four gears provided. Second is the logical choice for starting from rest, and from there the shift may be made into either of the higher gears.

For highway passing, third gear will give acceleration from 60 to 80 mph in 6 seconds. Fourth gear acceleration is remarkably consistent, just under 4 seconds for each 10 mph increment from 15 to 80 mph, where the torque peak is reached. Cruising speed is anything you can use, though here again the problem of piston speed intrudes itself. At 2500 fpm piston speed, the road velocity in fourth gear is 77.7; at 3000 feet per minute the road speed is 93 mph.

After the competition performances of the Jaguars at Le Mans, where the durability of the engine at sustained high revs was conclusively proven, the latter figure may safely be taken as a conservative cruising speed. In testing the coupe, sharp corners were negotiated with the throttle open in second gear. The stiffer suspension of the modified car held without skidding except when the driver was too careless to watch his speed on entering the corner. As shown in the specification table, the weight distribution is slightly to the rear, not enough to give the car tail-wagging characteristics, but sufficient to break the rear end loose before beginning a four-wheel drift.

It is difficult, even for the novice, to get into trouble with the Jaguar, though, as with any high-performance car, the accelerator must be trod on prudently, particularly on wet roads. The XK-120M ride should be experienced by the apologists for American soft suspension. Under 25 mph minor road shocks are more noticeable than they would be in an American car, but above that speed the stiffness is far more comfortable than any marshmallow ride ever can hope to be. Hand-written notes can actually be jotted down at cruising speeds and are fully as legible as those made at a desk. Brakes are fully adequate for cruising, and even for short competition events.

The early Jaguars had much trouble in this respect, with fade becoming increasingly evident after a few laps of the course. Current competition Jaguars, the factory C models, have tremendous brakes; the fact that these have not yet been handed down to the road cars is further indication that the factory does not regard the XK-120 or even the XK-120M as a true competition machine. In five years of production of the XK series, not one major engine or chassis change has been made in the stock models. There have been additions—the modifying kit for the engine and chassis, and two new body styles, a coupe and a convertible coupe. Performance wise it does not seem likely that a change ever will be required.

The Motor, writing in 1950, said about the stock XK-120 it had just tested: “So far above normal is the performance … that the pre-else figures can virtually be described as of scientific interest only… on the wide open spaces of track or motor road the ultimate speeds sustained are such that road tires can only be preserved intact with certainty if quite high inflation pressures are used.” In the next sentence the report makes it quite plain that the journal’s testers do not consider this performance unsafe in itself. And, of course, it isn’t.

But the consumer, even the special type who demands the exceptional road performance available in the Jaguar sports models, can hardly be expected to respond to further increases in top speed and acceleration. During the phenomenal run on October 20, 1953, when Norman Dewis recorded a speed of 172.4 mph in an XK-120M metal tonneau cover, 9-to-1 compression ratio and 2.92-to-1 (extra modifications included undershield, bubble canopy, rear-axle ratio), a sudden gust of wind pushed the car from its position astraddle of the white centerline to one side of the road.

To Dewis that was an incident; to the amateur driver it might well have been an accident. It is doubtful that any present Jaguar owner would care to trade in his present car for one capable of such high speed. In short, the real charm of the Jaguar is its high-speed cruising ability and its tremendous acceleration, both recognized safety factors. In the past two years other manufacturers have made serious attempts to match the Jaguar’s value in performance per dol- lar. One of William Lyons’ greatest contributions to the world is that he has made them try. His Jaguar XK 120 will live in auto history as the most influential car of the early postwar era.